Chapter06

1.General Principles of Scientific Research

1.1Scientific Research

According to Angers (1990, p. 2), scientific research can be understood as an adventurous endeavor encompassing a range of activities and experiences that involve risk and novelty. This journey takes place within the realm of science and is therefore not random; it follows a specific approach characterized by precision, methodology, and objectivity. Scientific research is simultaneously demanding and stimulating: demanding because it requires sustained effort, creativity, ingenuity, perseverance, and self-discipline; stimulating because it provides the joy of discovery, the opportunity to acquire new skills, the satisfaction of progress, and the fulfillment of successfully completing a significant project.

Scientific research is a dynamic process or a rational approach that enables the examination of phenomena and the resolution of problems, leading to precise answers through systematic investigation. This process is characterized by its systematic and rigorous nature, resulting in the generation of new knowledge. The objectives of research include describing, explaining, understanding, controlling, and predicting facts, phenomena, and behaviors. Scientific rigor is guided by the principle of objectivity, meaning that the researcher focuses solely on facts within a framework established by the scientific community.

1.2. Scientific knowledge :

Scientists often emphasize that they do not speak without evidence; instead, they rely on well-established facts. By this, they mean that scientific knowledge does not emerge from nowhere but is built upon existing theories and prior research. Scientific studies evaluate theories by gathering and analyzing data and evidence, then revising these theories according to the results obtained from new information. Through this process, knowledge accumulates and science advances. As a result, some hypotheses are discarded, while others are further examined to determine their ability to explain certain social phenomena.

In practice, research can take various forms. It may involve:

- Analyzing a significant or novel phenomenon

- Interpreting and critically evaluating a work or text

- Discussing and exploring a recurring issue in depth

- Shedding new light on an existing debate using fresh evidence

- Studying a specific topic or theme based on reconstructed or recent data

1.3. Functions and Objectives of Scientific Research:

Scientific research in the natural sciences can serve six major functions or objectives:

• Diagnosis:

This involves accurately characterizing the system, substance, or physical

phenomenon under investigation. In chemistry or physics, this may include

analyzing properties, defining experimental parameters, and identifying initial

conditions.

• Exploration:

Research also aims to explore unknown or poorly understood phenomena, gather

experimental data, observe reactions, measure physical variables, and identify

new behaviors of matter.

• Interpretation:

Based on observations and experimental results, researchers seek to interpret

phenomena using scientific laws, theoretical models, and fundamental equations.

This step helps explain underlying mechanisms and the scientific rationale

behind the findings.

• Prediction:

Natural sciences frequently aim to predict the behavior of systems using

established laws or mathematical models. Predictions may concern the evolution

of a chemical reaction, the behavior of a material, or the interactions between

particles under various conditions.

• Control:

By understanding the parameters affecting a phenomenon, research enables the

control and optimization of processes. In chemistry, this may include

maximizing reaction yield; in physics, stabilizing a system or regulating a reaction

by adjusting key variables.

• Archiving:

Research generates databases, protocols, and reproducible results that serve as

references for other scientists, contributing to the accumulation of knowledge

and the advancement of scientific disciplines.

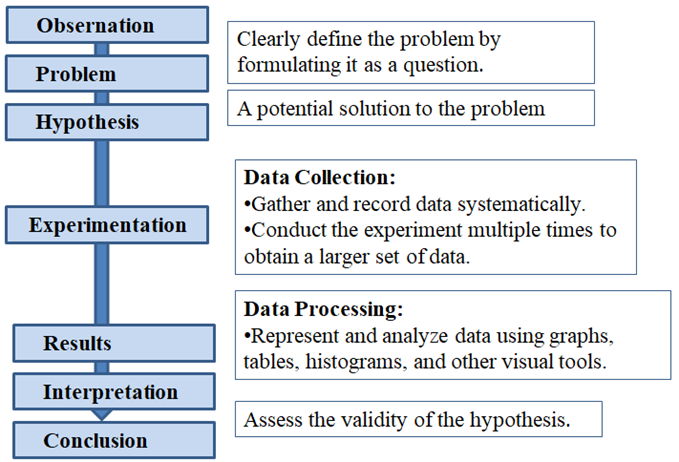

1.4. Steps of Scientific Research :

Any scientific process is required to proceed through a set of structured and sequential steps:

1. Observation – Identifying and examining phenomena or problems.

2. Hypothesis – Formulating a testable explanation or prediction.

3. Experimentation – Designing and conducting experiments to test the hypothesis.

4. Results – Collecting and analyzing data from experiments.

5. Interpretation – Making sense of the results and understanding what they indicate.

6. Conclusion – Drawing final conclusions based on the interpretation of results.

Figure 01: Representation of the Scientific Process

1.4.1.Observation

Every scientific theory originates from observation and questioning. This initial step can take various forms, including:

- Facts

- Models

- Theories

- Representations

- Beliefs

1.4.2.Formulation of a Hypothesis

1.4.2.1 Definitions

The hypothesis is the central element of the scientific method. It poses a question and proposes a tentative explanation, providing a possible solution to the problem identified through observation. A hypothesis often arises from a question that naturally follows from prior observations.

There are three main types of hypotheses frequently used in scientific research:

a. General (Conceptual) Hypothesis

- General hypotheses, also called theoretical hypotheses, are the most common type.

- They provide a tentative answer to a scientific problem, offering an explanation for a phenomenon.

- General hypotheses usually emerge from observations and aim to understand why a particular factor or variable produces a certain effect, without detailing the exact mechanisms.

b. Operational (Working) Hypothesis

- Operational hypotheses, also called working hypotheses, define more precisely the elements that will be manipulated or measured.

- While a general hypothesis identifies the expected effect of a factor or variable, the operational hypothesis specifies which factors will be studied and how they will be measured.

- This type of hypothesis is frequently used in experimental research in physics and chemistry.

- Operational hypotheses are often formulated using the "If… Then…" structure, where If introduces the conceptual assumption and Then indicates the verification procedure.

c. Statistical Hypothesis

- Statistical hypotheses, also known as “testable hypotheses,” are used to demonstrate, using statistical methods, whether the proposed hypothesis can be accepted or rejected.

- Numerical values obtained during experiments allow the researcher to verify the initial hypothesis quantitatively.

Claude Bernard emphasized the importance of hypothesis in science:

“Without a hypothesis, that is, without the mind’s anticipation of

facts, there is no science, and the day of the last hypothesis would be the

last day of science.”

“The experimental method, as a scientific method, relies entirely on the

experimental verification of a scientific hypothesis.”

1.4.3.Conducting an Experiment

To confirm or refute a hypothesis, it is necessary to carry out experiments. When testing a hypothesis experimentally, four fundamental rules should be followed:

- Test the effect of a single parameter by either removing it or varying its value.

- Keep all other parameters constant during the experiment to isolate the effect of the tested variable.

- Establish a control experiment for comparison. Without a control, the procedure is merely a manipulation, not a proper experiment.

- Repeat the experiment multiple times to ensure reproducibility of the results.

1.4.4. Analyzing Results

- Record and examine the results obtained from experiments.

- If multiple trials have been performed, compare them to ensure consistency.

- Organize and present the data using tables, graphs, diagrams, or descriptive text to facilitate interpretation.

1.4.5. Interpreting Results

- Once analyzed, results should be interpreted in relation to the initial hypothesis.

- If the interpretation aligns with the original observation, the hypothesis is validated.

- If the interpretation contradicts the hypothesis, it must be rejected or reformulated, and new experiments may be necessary.

- A single contradictory experiment does not allow generalization, while consistent confirmation across multiple experiments may lead to the formulation of a general rule or scientific law, valid until potentially refuted.

1.4.6. Drawing a Conclusion

- The final step is to conclude by summarizing the facts, hypothesis, experimental procedures, and interpretations, creating a coherent scientific narrative.

- Once validated, the hypothesis and supporting experiments are not the end; scientific inquiry requires continuous questioning and verification.

- Dissemination of results through scientific publications ensures that discoveries are shared, scrutinized, and integrated into the broader body of scientific knowledge.

1.5.Research Ethics in Scientific Studies

The primary objective of any researcher is to obtain information and data. However, not all methods of data collection are legal or ethical. Research ethics requires respecting the privacy of research participants, safeguarding their rights, honoring their opinions, and ensuring the safety of both participants and the researcher—under all circumstances.

While research ethics can sometimes limit access to information, contemporary scientific practice prioritizes ethical conduct over mere access to data.

Therefore, to ensure the protection of the rights of individuals and groups involved in scientific studies, no research can be conducted today without strictly adhering to established research ethics guidelines.

- Honesty and Avoiding Plagiarism: Researchers must report data and results truthfully, without falsification, selective reporting, or plagiarism. Using others’ work, ideas, or data without proper attribution is strictly prohibited. Clear explanations of the study’s objectives must be provided.

- Anonymity and Confidentiality: Participants’ identities and personal data must be protected. Sensitive data should be stored securely and destroyed after the study if necessary.

- Trust: Building trust with participants encourages accurate and reliable data collection.

- Informed Consent: Researchers must obtain participants’ consent before any data collection. Consent should clearly explain the study’s purpose, procedures, and participants’ rights.

- Right to Withdraw: Participants can withdraw at any time, and researchers should plan for potential dropouts to maintain adequate sample size.

- Recording and Imaging: No audio, photo, or video recordings should be made without prior informed consent.

- Avoiding Deception: Participants must not be given false expectations or promises. Compensation, if provided, should not be linked to research outcomes.

- Respect for Participants: Researchers must consider participants’ perspectives and ensure the study does not harm them physically or psychologically.

- Safety: The safety of both researchers and participants is paramount. Experiments should not pose undue risks.

- Feedback and Review: Participants may review the study findings before publication to ensure accurate representation of their contributions.

1.6.Types of Scientific Research :

In the exact sciences, the choice of research methodology depends on the research question, available resources, and practical constraints. Two conceptual approaches can be considered:

1.6.1Quantitative Approach: This is the primary methodology in the exact sciences. It involves measurements, experiments, and statistical analysis to obtain numerical data. For example, it can include measuring chemical concentrations, testing the effect of variables on physical phenomena, or analyzing large datasets.

1.6.2.Qualitative Approach: Although less common in the exact sciences, qualitative methods can complement quantitative research. They are used for descriptive observations or exploratory studies when phenomena cannot be directly quantified. For instance, this may involve observing ecological interactions, documenting crystal formation patterns, or describing complex experimental behaviors.

The choice of methodology may also be influenced by resources, team expertise, sample accessibility, and funding, as quantitative studies generally require more time, equipment, and financial investment than qualitative or descriptive studies.

|

Quantitative Research |

Qualitative Research |

|

Fully applicable in exact sciences |

Less common, complementary |

|

Experiments, precise measurements, statistical analysis, hypothesis testing |

Descriptive observations, exploratory studies |

|

Obtain numerical data for analysis to describe, predict, or control phenomena |

Understand phenomena not fully quantifiable |

|

Measuring chemical concentrations, testing variables in physics |

Observing ecological patterns, describing unexpected results, documenting complex biological behaviors |

1.6.3.Mixed-Methods Approach

The mixed-methods approach combines both quantitative and qualitative research methods.

- It allows the researcher to leverage the strengths of both approaches, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study.

- Quantitative methods offer precise measurements and statistical analysis, while qualitative methods, through observations, interviews, or protocols, provide rich descriptive information.

- The two approaches are complementary, not contradictory. Qualitative research is particularly useful in exploratory phases of a new study, especially when limited information is available about the subject.

- Using a mixed-methods approach helps the researcher to investigate the phenomenon in all its dimensions, combining depth (qualitative) and breadth (quantitative).

1.7. Different Approaches in Scientific Research:

1.7.1. Inductive Approach (Exact Sciences)

The inductive approach consists of building general principles, models, or empirical laws from repeated observations and experimental results. In the exact sciences, induction is often used in the early stages of research when scientists are exploring new phenomena or collecting data without a predefined theory. By identifying regular patterns—such as relationships between variables, recurring behaviors of materials, or consistent outcomes under controlled conditions—researchers can formulate empirical laws or hypotheses. Although induction provides valuable insights, it does not establish absolute certainty; rather, it offers probability-based generalizations that require further theoretical support and experimental verification.

1.7.2. Deductive Approach

The deductive approach begins with existing theories, axioms, or well-established scientific laws and uses logical reasoning to derive specific predictions or conclusions. This method is fundamental in fields such as mathematics, theoretical physics, and engineering, where researchers start from known principles and apply them to particular cases. For example, using Newton’s laws to predict the motion of an object, or applying thermodynamic equations to determine energy transfer in a system, are clearly deductive processes. Deduction ensures coherence, precision, and logical consistency in scientific reasoning, providing a reliable framework for interpreting and explaining experimental results.

1.7.3.Hypothetico-Deductive Approach

The hypothetico-deductive method is the dominant approach in modern scientific research, especially in physics, chemistry, and life sciences. In this method, scientists first formulate a hypothesis based on theoretical knowledge or preliminary observations. They then deduce testable predictions and design experiments or simulations to verify or falsify these predictions. If the results confirm the hypothesis, it strengthens the associated theory; if not, the hypothesis must be revised or rejected. This approach combines the strengths of both induction and deduction: induction helps generate hypotheses, while deduction provides a rigorous way to test them. It is essential for producing reliable, reproducible, and predictive scientific knowledge.

2.Ability to analyze a problem:

2.1.What is a Research Problem in Exact Sciences

- A research problem is a clearly defined scientific question arising from observations, experiments, or theoretical considerations.

- It expresses a phenomenon or a situation that requires explanation, measurement, or prediction.

- It may generate related sub-questions that guide the research process.

- It cannot be answered immediately or simply with “yes” or “no”; it requires systematic investigation.

- It leads to the formulation of testable hypotheses that the research aims to confirm or refute.

- It defines the scope of the study, the variables to be measured, and the methodology to be used.

- It determines the perspective or framework through which the phenomenon will be studied, whether experimental, computational, or theoretical.

2.2.1.Problem vs. Research Problem in Exact Sciences

- A problem generally refers to a question or challenge that needs resolution, either practical or theoretical.

- A research problem is a specific scientific question that can be addressed using logical, systematic, and reproducible methods, such as experimentation, modeling, simulation, or quantitative analysis.

2.2.2.Why is a Research Problem Important?

- It allows the researcher to effectively address the chosen scientific topic.

- It helps organize and plan the research work, keeping the study focused and avoiding irrelevant paths.

- It guides critical thinking about the subject and opens specific research directions to clarify the variables, parameters, or mechanisms that will be investigated.

- It establishes a link between the research object and the theoretical or empirical resources that will be used to study it.

2.2.3.How to Construct a Research Problem in Exact Sciences

- Transform the topic into a scientific question:

- Start from observations, experimental data, or known phenomena.

- Conduct a literature review using keywords to identify gaps or unresolved questions.

- List the most relevant questions based on these observations.

- Define the problem and its scope:

- Ask what makes this topic scientifically important.

- Identify the challenges, limitations, or unknowns in the topic.

- Determine the key variables, parameters, or mechanisms to study.

- Formulate hypotheses that aim to explain causes, effects, or relationships.

- Iterative process:

- A research problem often leads to further questions.

- This generates a continuous loop: hypothesis → experimentation → analysis → new questions → refined hypotheses.

- This iterative process ensures the problem is addressed rigorously and systematically.

2.2.4.How to Identify a Research Problem

- A research problem should be both original and relevant.

- One effective approach is to identify a “knowledge gap”, which represents an area where scientific understanding is incomplete.

- In exact sciences, a research problem emerges from reviewing the literature or observing phenomena in experiments or the field, leading to a research question and a testable hypothesis.

a.Identifying a Research Problem Through a Knowledge Gap

- A knowledge gap refers to a missing piece of scientific knowledge or an aspect of a phenomenon that has not been adequately studied.

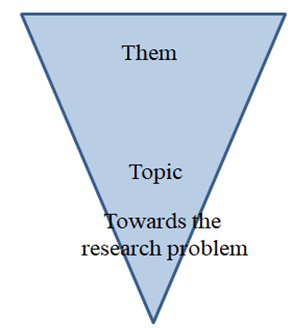

b.The Conical (Funnel) Method

- Start from a broad scientific topic and gradually narrow it down to a specific problem or question.

- This method helps focus on a precise and testable research problem.

Figure 3: Conical Method for Defining the Research Problem

c.Considering Study Limitations

- Review the discussion or conclusion sections of scientific papers to identify:

- Limitations of previous studies.

- Recommendations for future research.

- These elements often reveal gaps in current knowledge.

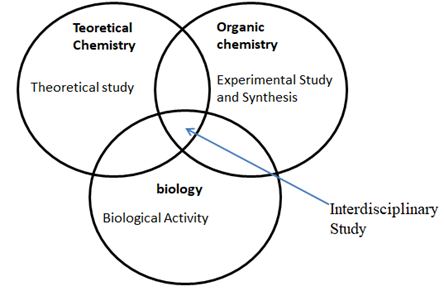

d.The Circular (Interdisciplinary) Method

- Combine themes or concepts from multiple fields or disciplines, whether strictly academic or applied.

- A knowledge gap can often be found at the intersection of these domains, providing opportunities for novel and impactful research.

Figure 3: Circular Method in Scientific Research

2.2.5.The Research Problem in a Thesis Topic

- Once a research problem is identified, the researcher must check if a solution or answer already exists.

- If the problem seems to have an obvious solution, the chosen problem may be inappropriate or trivial.

- Constructing a research topic usually leads to insights beyond initial expectations.

- The research will fit within a specific scientific or experimental domain, and the focus will gradually narrow, similar to a funnel method.

- The choice of topic should be justified based on scientific relevance and practical or personal interest.

- Hierarchizing questions and sub-problems helps define the research problem clearly.

2.2.6. Formulating the Research Problem

- The formulation should stimulate scientific reasoning and inquiry, using prompts such as: “to what extent…,” “how…,” “in what way….”

- A well-formulated research problem in exact sciences includes:

- A central question and several sub-questions.

- A problem to solve with hypotheses to test.

- Systematic reasoning, experimentation, and analysis to validate or refute the hypotheses.

- Proper formulation reflects the researcher’s ability to structure and guide the study, not merely to convince.

- A strong research problem is innovative, focused, and contributes to knowledge.

- Tools like mind maps can help visually organize ideas and stimulate systematic thinking.

2.2.7. Evaluating the Research Problem

- To self-assess, ask:

- Does my problem contribute something new to the field?

- Does it avoid providing an answer in its own formulation?

- Is it sufficiently precise and testable?

2.2.8.Conclusion

A well-formulated research problem stimulates scientific reasoning and often leads to additional questions and new perspectives.

- It is not limited to a question with an obvious answer; instead, it guides the investigation and opens new research directions.

- It provides a platform for discussion, reflecting both the complexity of the research topic and the variety of possible approaches to achieve a meaningful, accurate, and relevant solution.